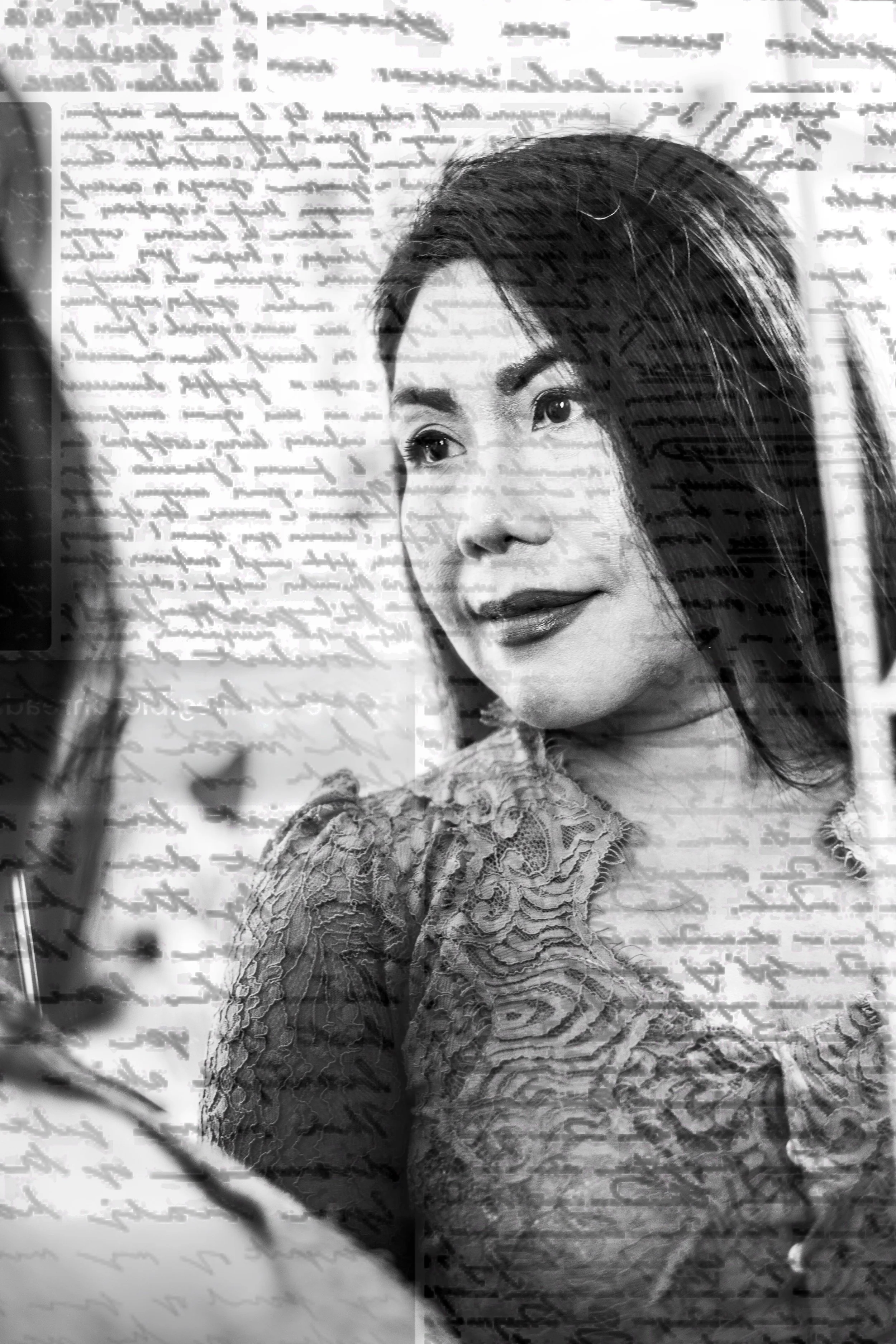

Rini Martindill

Rini was born in Surabaya, East Java Indonesia and met her Tasmanian husband Thomas who as in the Australian Navy.

She married him and had an Indonesian and Australian wedding. Both were very different she said, in Indonesia I had a Royal wedding with 24 bridesmaids!

Rini invited me to her house in Blackman’s Bay where she hosted a lunch for about 15 of her Indonesian girlfriends. The dining table was filled with many authentic Indonesian dishes and most contained chilli.

One thing that’s seemed different was the absence of alcohol. ‘For us it’s all about the food’ Rini says. That’s almost the opposite in Australia I thought! In Indonesia there’s a strong sense of community and sharing food.

In Islam, the consumption of alcohol is haram (forbidden) because it is considered an intoxicant and is seen as harmful to the mind.

This prohibition is based on the Quran, which refers to intoxicants as "the work of Satan," and is supported by the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad. The prohibition extends beyond just drinking to include other actions related to alcohol, such as selling, transporting, and serving it. ‘When you grow up with certain beliefs it’s difficult to change’, Rini says.

Rini loves the beauty and nature of Tasmania and the spaciousness, her house has beautiful views of Blackman’s Bay.

‘I come from the big city, the Surabaya metropolitan area has a population exceeding 10 million people, making it the second-largest metropolitan area in Indonesia. In Java there are as many as 20 dialects,’ Rini says..

When I first arrived here in in 2009 I wanted to go shopping but I was shocked when Thomas told me the shops in Hobart all closed at 5pm!’, Rini explains.

Rini operates a beauty therapy business in Hobart. ‘Most of my clientele are very polite. On one occasion a woman came in and asked for a therapist who was an Australian girl then asked to speak to the manager. ‘I am the owner and manager’ she stated to the woman’s disbelief. ‘When she took the time to get to know me she was fine,’ Rini explains.

The Portraits

When practical the formal Faces From Our Town photographic portraits were produced in the school workshops with the students.

The students were shown how to produce powerful portraits using simple lighting and camera techniques, interesting composition and simple props.

Individuals chosen for the formal portraits were carefully selected by each school community, a Palawa adviser, The Tasmanian Art Teachers Association (TATA), the Students Against Racism group, the Migrant Resource Centre, the Department for Education of Students and Young People, the participating schools and local councils.

Major themes and goals examined through the series of portraits and stories include promoting equality, the value of multiculturalism and immigration, combating racism and discrimination, promoting empathy and compassion and adding to community cohesion.

The portraits also examine photographic portraiture’s role in defining Australia’s social history and identity.

Students learnt how to plan ideas and think creatively and were given workbooks which guided them through the portrait workshop.

What is a portrait?

The portraits reflected on the work of photographic artists from the Dada, Surrealist and Pop Art movements. These pioneers such as Man Ray, David Hockney and Bill Brandt changed the way photography was seen just as a mirror with a memory - simply a form of documentation, to a creative medium where interpretation and experimentation and creative expression and inventive techniques such as solarisation and wide angle lens distortion and multi-view portraits were used.

Arun Pratap

Arun was born in Fiji off Indian decent. He has nine other siblings. He grew up on a sugar cane plantation started by his great grandparents.

The history of Indians in Fiji began in 1879 when the British colonial administration brought 60,000 Indian indentured laborers to work on sugar plantations, an experience known as Gurmit. These individuals were called Girmitayas. Workers faced harsh conditions and limited rights under overseers and estate managers. However, many chose to stay in Fiji after their contracts expired, establishing a distinct Indo-Fijian culture. Fiji gained independence in 1970.

‘The whole family worked long days on our sugar plantation to achieve success, unlike Australia there was no social security’, Arun explains.

‘Social security has its benefits and downfalls, it can make people lazy and unmotivated if they know there’s always someone to back them up,’ Arun suggests.

Arun speaks Hindi, Fijian and English. His parents focus was on quality education so Arun studied hard and received a bachelor degree in physics and medicine and education.

Arun’s brother was already teaching in Tasmania and suggested he do the same. He had two small girls and wanted them to grow up in Tasmania rather than the busier cities like Sydney and Melbourne. Arun was offered a teaching job in St Marys on Tasmania’s east coast. ‘I arrived on a Saturday and was rostered on the Monday’ Arun recalls. ‘All my possessions were still in a shipping container! Arun explains.’

Arun says he felt very welcomed when he arrived in Tasmania. He quite likes the cooler climate but does miss the exotic foods and swimming in the ocean any time of the year he enjoyed in tropical Fiji.

Arun has been in the Riverside Lions Club for the past 15 years and recently became the president. Arun suggests that if you get involved in Tasmanian life and try to give back, you will be rewarded, respected and accepted.

Georgina Richmond

Born in the United Kingdom in 1964, Georgina has always been interested in vintage clothing. When she was just 14, she would attend the iconic Kite Market in an old area of Cambridge and she loved to visit jumble sales with friends to pick up amazing collectables.

‘I come from an African and English heritage,’ she says. ‘There was racism in England in those days. I was called horrible names and I felt very different.’

‘I grew up in a very artistic family,’ Georgina says. ‘My granddad was an artist and an engraver. Creativity was always encouraged so I was always drawing and painting.

I went to Cheltenham Art School in Gloucestershire and did a BA in sculpture and painting. I met my partner Michael in 1985 and followed him back to Australia.’

When Georgina came to Tasmania, she says there weren’t many people of colour here.

‘People would tell me I must be Aboriginal,’ she says. ‘I was never asked about my heritage, it was a different kind of racism. I had no friends and I felt very isolated. Thankfully Tassie has got a lot better and is much more multicultural now.’

After coming to Hobart, Michael and Georgina rented in Battery Point. They could see a business opportunity at Salamanca Market so they put a rug on the pavement and sold various books and collectables.

‘We made $100 at the first market and we celebrated out with a slap-up dinner.,’ she says. ‘As our sales built up we were offered the chance to join the Kookaburra antiques shop on the corner of Hampden Road. I sold vintage clothes and Michael handled the books. It was a fantastic thriving business. We were at Kookaburra and Salamanca Market for 25 years.

We love living in South Hobart so purchased a house in Wellesley Street and we often walk along the track to the Waterworks Reserve.

I had singing lessons for 10 years with local vocal coach Helen Todd and I began performing Celtic songs and learned the harp,’ she says. ‘I was in the EHOS opera and was asked to join a Flamenco group, so had to learn Spanish songs.’

Georgina’s artistic talent saw her enter the John Glover art prize 12 years ago and her work has been accepted twice. She has exhibited at the INCA gallery and now exhibits at Wild Island Gallery in Salamanca Place. She recently complete a series on SoHo and kunanyi and wants to have an exhibition every year.

Yasuko Mizushima

As a 19 year old Yasuko visited Tasmania and fell in love with its nature and pace of life.

Years later she was a single mum and migrated under a three year Multiple Entry Visitor Visa. This meant her daughter could go to school but Yasuko couldn’t work for three years. ‘It was a struggle’ she said, ‘I had to use all my savings’.

Yasuko loved food so opened a successful Japanese restaurant in Battery Point, Hobart. People would enjoy coming to her restaurant knowing she was Japanese making authentic Japanese cuisine.

Yasuko says food has the power to unite people across different social classes, backgrounds and relationships, by providing a common ground for connection and shared experience.

Yasuko says the migration level in Japan was very low so she had little concept of racism. I think Tasmanians generally have a warm welcome for Japanese people. However she has Asian University friends who have been yelled at and had eggs thrown at them on the streets of Sandy Bay.

Samsita

Sasmita came from South Africa where historically racism was a dominant force in the South African culture. Thirty years since the end of Apartheid, South Africa still grapples with its legacy. Unequal access to education, unequal pay, segregated communities and massive economic disparities persists, much of it is reinforced by existing institutions and attitudes. How is it that racism and its accompanying discrimination continues to hold such sway in this, majority Black populated and Black governed nation?

Sasmita is of Indian decent and came to escape the racism and violence she experienced in South Africa, she was looking for a fresh start.

A qualified hairdresser she commenced work in the Hobart suburbs.

I really enjoyed living in Tasmania, its open spaces and wonderful environment and feeling of unrestricted freedom and safety.

However at the salon some customers refused a haircut by me and openly asked for a white person. This was quite shocking and hurtful and very unexpected.

‘I think in some areas of Tasmania people are ignorant and fearful of what they don’t understand,’ Samsita suggests.

Pushpa Kunasegaran

Pushpa’s family originally migrated from southern India to Singapore where she grew up, so her journey to Tasmania is a part of her migration story.

‘We migrated to Tasmania 20 years ago when there were very few Indian people here - we really stood out,’ Pushpa explains.

‘I don’t know if everyday Tasmanians are aware of how expensive it is to study in Tasmania. We have spent close to one million dollars on education which has gone back into the Tasmanian economy.

When we moved here my husband was only permitted to work 20 hours a week, which wasn’t enough, so he returned to Singapore to work for a while – this ended up being 17 years! That’s what you call a long term relationship. We are all together now in Tasmania.

I always tell migrants that you have to assimilate and mix with locals, then you’ll have the best of both cultures.

What I find interesting about Tasmanian life is the way families embrace nature by going bushwalking or to the beach or fishing and boating. I’m also amazed by the work ethic and tenacity of Tasmanian women. In my culture new mums would have a nanny for the first three months to help with the new baby. I’m often amazed when women here return to work so soon after child birth!

I find most people in Tasmania are actually very welcoming and respectful of those who are in the minority, Pushpa says’.

Pushpa is a teacher at a Launceston College. ‘My curious students often ask me what does the red dot on your forehead signify? I tell them that in our culture it means I’m married.

When my children were young they were taught to address all older people as Uncle and Aunty. This became quite humorous when they would visits their young friends’ house and they’d call their friends’ parents Aunty and Uncle. Their friends would ask, ‘Why did you call my dad Uncle - you’re not related to us!’

Montz Matsumoto

Montz was born in a small village in Japan and started to learn bluegrass banjo from the age of 15. ‘When I was young I romanticised about American culture and that’s where the fascination for the banjo came from,’ Montz says.

He also explains that the banjo is similar to the shamisen, a Japanese three-stringed plucked instrument. It is constructed with a neck and strings stretched across a sound box to amplify the sound. Like the shamisen, the banjo has a skin head and a resonating base that act together like a speaker.

In 1987 Montz joined the legendary Japanese folk group, The Natasha Seven. Montz came to Australia in 2002, and spent many years busking and performing at folk and bluegrass festivals.

He visited Tasmania 12 years ago and fell in love with the climate and topography.

‘Compared to South Australia, which is so dry and hot, in Tassie I saw forests, water and hills, very similar to many landscapes in Japan,’ he says. ‘I also enjoyed the overcast and cloudy days and when I discovered that Cygnet had its own folk festival, I thought this must be a great place!’

Montz lives a modest self-sustaining life in a forest near Cradoc. His music is a mix of some original Japanese songs as well as Celtic and Bluegrass styles.

‘I’m always exploring,’ he says. ‘Naturally my own culture comes out organically in my music, married with my experiences of living in the Huon. Reflections of my life journey and thoughts on how people enter and leave my life all feed my creativity.’

The Cygnet Folk Festival is one of Australia’s most iconic folk music festivals. It’s very highly regarded by musicians and festival-goers from all over Australia and overseas.

The Festival is a showcase of eclectic music genres featuring both local and international talent, dance, poetry, masterclasses, film, kids' entertainment, food, wine, art and local handicrafts all set in the breathtaking scenery of Tasmania's Huon Valley.

Montz says he has never really experienced racism here. Maybe it’s because the community are exposed to people from different backgrounds and nationalities and they learn that through music difference can be celebrated.

Montz says there are many cultural differences between Tasmanian and Japan. ‘In Japan we eat within the seasons, even seafood has a season, we eat a lot more vegetables in Japan than Tasmania, the idea of eating a meat pie on its own is bizarre to me’, Montz says.

‘When it recently snowed down to street level everything stopped, schools were cancelled. But the snow was only 2cm deep!

When it’s hot in Japan we eat colder food including cold noodles. I was invited to a Christmas lunch when it was very hot and the guests served hot roasted foods and gravy which surprised me, I guess it’s a throwback to England when Christmas is very cold’, Montz laughs.

Montz thinks young peoples’ view of the world through the over exposure to social media is distorted, dividing and damaging and does not promote social cohesion.

Titin Ratna Wahyuni

Tintin lives in a village near Malang, a city in East Java, Indonesia. Prized by the Dutch for its mild highland climate, the city retains much of its colonial architecture. The Balai Kota building blends Indonesian and Dutch styles, and grand mansions line the main boulevard, Jalan Besar Ijen. North of the city, the Buddhist-Hindu Singosari Temple ruins are a remnant of a medieval kingdom. To the east is Mt. Bromo, a volcano with hiking trails. Malang is a Jewel of the Eastern Highlands and rated Indonesia’s most charming and relaxing city. Titin speaks five languages and was a teacher.

It’s a different style of eating in Indonesia, the woman normally cooks various dishes and leaves them out all day for people to graze on. The house is always open and if people are hungry they can drop in – no one goes hungry’, Titin says. ‘There is a lot of street food, I thought it strange that when I went to a restaurant in Tasmania I had to order just one main course!

When I came to Tasmania I wanted to open a shop at the front of our house, this is how it works in Indonesia—I was not used to all the permits and red tape in a Australia!

I find the Australian attitude to tanning fascinating and funny. I pulled up to a tanning clinic in Magnet Court, Sandy Bay which said – ‘come in white and we’ll turn you black’. It’s the opposite in Indonesia - we hide from the sun and want to keep a pale complexion’ Titin laughs. Titin worked for many years in a very popular restaurant in Sandy Bay. One day two older local Sandy Bay women came in then left because they didn’t want me to serve them, I was quite confused.

The most important law in Indonesia is that you must align with just one religion and we pray five times a day. I am Muslim but if my Aussie husband John said he was an atheist he could be imprisoned! In Indonesia if married women travel outside your home you must wear a hijab head dress. I like it that in Australia things are very open and free and women can wear what they want and you can protest about what you like.

When I first arrived here I couldn’t understand Australian slang. I would ask them to speak English please!......it’s too quick.

People used to say ‘no problem’......and I didn’t understand what they meant...all I heard was ‘problem’.....what was the ‘problem’ I thought? Titin laughs.’

Titin operates a very successful Indonesian Martabak street food stall at the Hobart Sunday market which sells fresh produce, artisan and street food. People love her tasty Indonesian street style food which she prepares to order. Located on Bathurst Street between Elizabeth and Murray Streets and held every Sunday from 8:30 AM to 1:00 PM its considered one of the top farmers' markets in the country.

Renata Pasieczny

Renata’s father Henry migrated from Poland in 1950s to work in the Hydro Electric Scheme at Tarraleah in central Tasmania. The working conditions were often very harsh and isolated.

Henry’s father suggested he contact a lovely Polish girl in Poland with the view to marriage. After many letters Anna arrived in Tasmania twelve months later and within six weeks they were married. Within four years they had four children.

Neither of them spoke much English.

Renata was born Renia but changed her name so people could more easily pronounce it. This didn’t actually help that much because students still teased her about her unusual name.

‘The teasing and bullying didn’t stop’ Renata says. ‘My life at school was very difficult’ and she didn’t enjoy her school years.

Because Renata spoke Polish at home, she went to school to learn English which she says was really difficult. From the age of five Renata was teaching her parents English as she learnt it. Renata was also attending Polish school to learn Polish and participated in Polish dancing and cultural events as well as Polish Girl Guides and Brownies.

Her mum went off to work at the Carlyle Hotel in Glenorchy without any English. There was a strong emphasis on studying and learning to benefit from free education, so Renata’s parents invested in two sets of encyclopedias. Her family house in Glenorchy was small so she shared her room with her three sisters.

Renata grew up in a catholic family and attended Polish church, she even has a photo of her being confirmed by the Polish born Pope John Paul the second when he visited Tasmania.

Renata’s school lunchbox was filled with Polish delicacies including Ukrainian sausage and dark brown pumpernickel bread. Her lunch smelt weird compared her Aussie schoolmates, she says. She dreamed of white bread sandwiches with Belgium sausage and lashings of tomato sauce. Renata says she didn’t really want to be considered different but just wanted to fit it and be like her Aussie classmates.

Renata is now a very successful hypnotherapist, psychotherapist and counsellor and uses her lived experiences which informs her work with her clients including migrants to Australia.

Robbie Gilligan

Robbie Gilligan says there’s a Celtic connection with Scotland and Tasmania. 40% of all Tasmanian’s have a convict ancestor. One of Tasmania’s most famous Scotsman is the photographer John Watt Beattie who immigrated from Aberdeen Scotland in 1870. Beattie was a pioneering landscape and government photographer who became Tasmania’s most famous photographers.

Robbie has a very strong Glaswegian accent and he says people ask him daily to repeat what he has just said. ‘It happens ALL THE TIME!’, Robbie explains with a grin...

‘I guess it’s good marketing for a Scotsman to own whisky distillery. People love my kilt, whenever there’s a Tourism Tasmania event they always ask me to wear it,’ Robbie laughs. ‘I have empathy for people who come to Tassie from another place and have to learn the language, I know how they feel! And yes, there is a Tasmanian State Tartan, and you can find it in various products like kilts, ties, and other accessories. The tartan was designed in 1988 and is inspired by the Tasmanian landscape, featuring colours like black, grey, green, red, and yellow.

Robbie and wife also make liqueurs from Tasmanian produce. The hazelnut liqueur is made from Tasmanian Hazelbrae hazelnuts and is delicious!

The Derwent Distillery name comes the distilleries location at Dromedary on the Derwent River. The extra humidity caused by the famous Jerry, unique riverside weather conditions and Tasmania's pristine air create the perfect location for single malt whisky maturation. The distillery’s name also honours the Derwent Distillery one of the first legalised distilleries in Tasmania, originally set up on the banks of the Hobart Rivulet in Gore St, South Hobart in the early 1820s.

On January 22, 1820, the Hobart Town Gazette reported, ‘The foundations of an extensive brewery were laid in the presence of a number of persons by R. W. Loane’. In December of 1823 the building was operating as the ‘Derwent Distillery’.

A change in colonial government policy saw Lt Gov Franklin introduce legislation to abolish the local distilling industry in 1838. If not for this action the Tasmanian spirit industry would have rivalled Scotland which only had its first legal distillery in the 1830s.

Robbie has spent some time camping and trout fishing and tasting a wee dram with whisky icon Bill Lark at the highland lakes. ‘It’s beautiful like Scotland’s highlands but a wee bit more rocky’, Robbie says. Whisky is something you savour, it’s not all about getting drunk. In Gaelic, its name loosely translates to “water of life.”

Moderate whisky consumption claims health benefits. In 16th-century Scotland, apothecaries sold whiskey as a tonic to slow aging, cure congestion, and relieve joint pain. During American Prohibition, doctors prescribed whiskey to treat pneumonia, high blood pressure, and tuberculosis.

Kris Shaeffer

Kris studied art at the first Hobart University at domain house campus in the late 1960s and is a first nations woman with a deep spiritual connection to the land. Kris says Palawa people were deeply connected to the land, which they considered their cullaminna (mother of all life). Kris explains that the Palawa had seven seasons which evolved around when food was in season. Their lifestyle included foraging and hunting for seasonal foods including wallabies, wombat, echidna, Tasmanian emu, possums, seabirds, and fish in winter; shellfish, Yolla( mutton-bird), seal, whale and various plants like sea parsley and sea celery, sea fig in summer; and native fruits like climbing blue berry, snow berry and native cherries in spring and autumn. Kris says Palawa have been in Lutruwita (Tasmania) for 70,000 years and survived two ice ages, they were resilient and resourceful and learnt to maintain a sustainable balance which respected the natural ecology.

First nation people have an unsevered connection with country and ancestors and through aboriginal dreaming and story telling a rich spiritual connection to ancestors is passed on and maintained. Kris believes places can hold spiritual memories of past events and she has seen and felt ancestorial spirits in vivid dreams in various Tasmanian locations. Kris suggests the ancient hunting and gathering process is a continuance of the dreaming and learning.

Kris is well known as an indigenous horticulturalist and designer of indigenous gardens. She has been working with nature to build a garden 450 metres above sea level at Neika South of Hobart. ‘Being above the snow line, there’s a ‘lovely, cool wet forest atmosphere,’ Kris says. The garden attracts wildlife including bettongs, bandicoots, potoroos, and pademelons and there’s even a devil’s den under the house! Kris believe its using Indigenous land practices and plant selection that has made the garden so beautiful. Many of the plants are now self-seeding and are a wonderful cornucopia of rare Tasmanian native plants.

Kris says her greatest influences were her wonderful parents who taught her bush, hunting, fishing, survival and building skills. Her mother received an order of Australia for her research in Tasmanian history and genealogy.

Kris grew up in Fern Tree and has mixed memories of her school life at Macquarie Street school in South Hobart. ‘I spent many days wagging school as I was picked on and called Abo and Boong and other hurtful names,’ Kris explains.

Today Kris is strong on social justice and reconciliation so to create a deeper understanding of indigenous history. She has spent 48 years in Tasmania teaching young people the history and culture of aboriginal people through art, dance, theatre and exploring nature and bush food. She has also created healing gardens to promote healing and respect.

Kris also has a studio space in a converted shearer’s shed at Avoca where she is completing a retrospective exhibition at a St Marys gallery. The exhibition includes three Noka treasure chests, Noka is the name for gift or treasure. The chests comprise the personal, the private and the hidden to be revealed only by invitation. They include fine art, beautiful hand bound journals and note books, and decades of teaching resources of aboriginal culture.

Salong Gamandi

‘My mum married an Australian man and we moved to Tasmania when I was four. She was quite poor so she was happy that I’d have a good education and more opportunities in Tasmania.

When I arrived I spoke Tagalog which is spoken by the ethnic Tagalog people in the Philippines and is one of the country's two official languages, alongside English. The name "Tagalog" comes from taga-ilog, meaning “river dweller". I quick forgot the Tagalog language. Learning English was easy for me as I was so young.

We go back to the Philippines every year to my mum’s small village in the mountains. I enjoy seeing my cousins when I go back. We eat more home cooked food and less junk food and it’s very family orientated. I’m actually a bit annoyed that I lost my knowledge of the Pilipino language, it would make it a lot easier when I go back!’ Salong explains.

‘I live in a small country town and felt accepted at my first primary school but at high school that all changed. Some students were cruel and judgemental. It took them a year to get used to me and now I have many good friends. I’ve blocked out any negativity.

In the Philippines they discriminated against my Australian father so I guess there is racism everywhere.

I’m completing year 10 and am excited about my future, my goal is to study to be a nurse’ Salong says.

Fontane Chung and Family

Chinese settlement in Tasmania began in the 1830s with the arrival of nine Chinese carpenters. During the tin-mining boom of the 1870s and ’80s, when there were 40 Chinese-owned tin-mining leases operating, Tassie’s Chinese population of 1500 (1.3 per cent of the then-total population) mostly lived in the rural north-east. Almost all came from China’s Guangdong Province.

A sign in a Derby cemetery explains the culture clash between Chinese migrants and Europeans who tried to “Christianise” the “heathens” and explains the reasons why the European graves all face east while the Chinese graves face west.

By the time of the 1881 census, there were 874 Chinese living in Tasmania, nearly all tin miners. During the next ten years the number fluctuated around 1000, though some moved out of mining; by the time of the 1891 census, 12 percent were market gardeners. For two decades the Chinese outnumbered the Germans as the largest group of migrants in Tasmania with a non-English speaking background.

In the 2021 census, 12,300 people in Tasmania – about 2 per cent of the state’s population – reported having Chinese ancestry.

In 1901 the Immigration Restriction Act, also referred to as the White Australia Policy, was enacted shortly after Australia's federation and was designed to restrict the number of Asian immigrants.

All potential non-European migrants had to pass a dictation test. A key tool for exclusion, the test required non-European immigrants to write a passage in a European language, which was often a language they didn’t know, making it nearly impossible to pass. The white Australia policy criteria changed in the 1950s when the Australian government needed workers for large infrastructure project like the Hydroelectric Scheme.

Fontane Chung’s grandfather Scott Chung came to Tasmania in 1955 and was sponsored by his uncle, a market gardener in Richmond. Looking for a business opportunity he took over the Launceston Lew’s Cafe restaurant at 203 Charles Street in the 1961, he renamed it the Canton and ran it with his three Chinese brothers who were also market gardeners.

Australian immigration made him wait 15 years before he could bring out his family so Fontaine’s mum Dianne didn’t see her father till 1970 when she was 15. ‘It’s the sacrifice he had to make if he wanted a better life in Australia’, Diane explains.

Fontane Chung and chef husband Sonny Yang purchased the Canton restaurant in Launceston from her parents Dianna and Noel Chung in 2006. Dianna and Noel purchased the Canton in the 1986 from Dianna’s father Scott Chung so there’s been a restaurant in these same location for at least 62 years. Today the Canton is a third generation restaurant and Tasmania’s oldest. It may even be the oldest Chinese in Australia! as the Toi Shan in Bendigo, Victoria recently closed after 77 years.

Fontane’s father Noel is a first generation Tasmanian born in Hobart. Noel went to school in Hobart and learnt Cantonese at home. Their family had a large market garden in Glenorchy and his brothers and relatives had restaurants in Sandy Bay, Hobart, Kingston and North Hobart. ‘The strength of the family unit has kept us going’. Noel says. ‘It’s the same for Greek and Italian shops and restaurants.

We’ve had to adapt to what the customer wants. In the 1960s the Canton opened till 3am so customers could eat after the pubs closed at 11pm. In the 70s when we took over we had to diversify the menu, 30% was Australian style foods to cater for the customer’s taste. Keeping a business going over many decades has had its challenges. Paul Keating’s recession in the 1980s, the airline dispute in 1990 changed the way people did business and most recently Covid’. Noel explains.

Noel grew up in Hobart and tells me he encountered racism at an elite Hobart school. ‘There was a bit of snobbery from the Sandy Bay students who arrived to school in Mercedes and BMWs and I arrived in a ute full of vegies’ Noel laughs. ‘You simply learnt resilience and tolerated racism’ Noel explains. His daughter Fontane went to school in Launceston and says she had a couple of racist students at school, so she made a point of making friends with them.

The Canton’s was last renovated in the 1980s. The interior has lovely wallpaper with a gold Bamboo relief and ornate lantern lights which creates a charming and authentic atmosphere for dining out. The front street sign dates back to the 1970s. Noel has a wonderful original Canton restaurant menu in pounds and pence.

Sonny and Fontane met at the restaurant where they both worked as kitchen hands. Today Fontane and Sonny manage the restaurant while her mum Dianne is the babysitter. After 62 years the Canton has wonderful and loyal patrons. Fontane says about 70% of their guests are regulars so they don’t need a menu as they come for the same things.

Some guests come and ask for their grandfather’s favourite dish that’s not on the current menu - so the chef has to be prepared for unusual requests. Fontane says they’ve even have had customers come from Flinders Island to take food home!

* Image: L-R Dianne and Noel Chung, Sonny Yang and Fontane Chung.

Neriiya Kadisha

Neriiya’s parents came from the Democratic Republic of Congo where Neriiya was born. Her parents were looking for abetter life for Neriiya and her two sisters.

In the Republic of Congo they speak Bantu and French as they were once a French colony.

In the late 19th century France colonised the region and incorporated it into French Equatorial Africa. The Republic of the Congo was established in 1958 and gained independence from France in 1960.

The Congo is on the equator so it's climate is primarily tropical and hot and humid, but it varies across the large country due to its diverse geography.

Neriiya arrived in Tasmania when she was three and mostly spoke French and then learnt English at school.

‘I know that I look different but I’m fine with that. I grew up with most of my classmates from my first day at school so I’ve never really experienced racism or had any bad experiences, perhaps going to a catholic school where compassion and acceptance are an important part of the catholic ethos has helped’ Neriiya explains.

Neriiya enjoys studying media arts the exploring her creative side. She hopes to become a dermatologist or midwife when she completes her studies.

Rabin Sapkot

Rabin was born in a small village called Padampur located inside the Chitwan National Park in Nepal. The village was moved in 1973 to allow for the establishment of Chitwan National Park, Nepal's first national park. The UNESCO World Heritage Site which has a subtropical climate with distinct seasons is known for abundant wildlife like one-horned rhinos, Bengal tigers, crocodiles, monkeys, and hundreds of bird species, offering jungle safaris for incredible wildlife viewing in its dense forests and grassy plains. The park provides crucial habitat for endangered species and a glimpse into the Tharu culture, making it a prime ecotourism destination in south-central Nepal.

Because of its rugged topography and many isolated villages and regions Nepal has over 120 languages but Nepali is the common tongue. It’s similar to Hindi but distinct, and written in the same script.

After leaving school it was Rabin’s his dream to better himself so

studied Tourism and travel and worked in hospitality and marketing in the UK for five years.

Nepal has historical connection with Nepal. Gurkhas.

When Rabin returned to Nepal he was 24 and restless and together with his wife Unissa they thought about moving again. They had friends in Australia who suggested they come.

They were tired of the busyness of the cities in London so decided to come to Tasmania. Rabin Came to Utas to complete a master’s degree in international business and public accounting. He was allowed to work 20 hours a week.

If you want to become a Australian you have to give up your Nepalese residency. His wife and two boys 6 and 4 now have their residency.

‘Tasmania is now home. Its similar and different in many ways to Nepal, there’s a strong sense in community in Tasmania like my small village in Nepal’ Rabin explains.

Rabin says he hasn’t had any significant racial abuse but he knows of many incidents in some suburbs where Nepalese and Indian shop owners have been openly physically and verbally targeted and even attacked.

Rabin thinks racism exists because many people haven’t travelled or been exposed to people from different cultures. He’s noticed a positive change in the last ten years where people are more friendly and tolerant.

Rabin says Tasmanians are very fortunate to have HECS where they can defer their Uni fee payments.

‘My degree cost $60,000 which is about four times more than what Tasmanians would pay. My wife and I worked five years fulltime to pay the money back. We also feel it’s our responsibility to help our parents in Nepal as the pension in Nepal is not enough to survive on, so our parents rely on assistance’, Rabin explains.

Rabin goes home every couple of years and his parents come every other year. ‘I think it’s important for my two boys to know their culture. I feel proud when the boys go back to Nepal and they naturally pick up Nepali again’ Rabin explains.

Rabin is a well-known and much loved face in the Hobart hospitality industry and has worked for a restaurant group for ten years. He also has his own small catering business at local festivals. His stall Ekka showcases untapped flavours from Nepal and India, from the foothills of the majestic Himalayas of Northern Nepal to the tropical Indian region of the South. Ekka is the brain child of Rabin and his brother Nabin. Ekka debuted at Tasmania’s Taste of Summer 24/25 and it quickly became an institution with the brothers returning again to delight festival goers in 25/26 with their delicious and diverse menu. Rabin says food is a fantastic way to share culture.

.

Carleeta Thomas

Story in progress. :-)

Acknowledgement of Country

In recognition of the deep history and culture of this island, the Faces From Our Town project acknowledges Tasmanian Aboriginal people, the original and continuing custodians of the Land, Sea and Sky. We acknowledge and pay our respects to all Aboriginal people of Lutruwita, all of whom have survived invasion and dispossession and continue to maintain their identity, culture and Aboriginal rights.